The phrase “doomscrolling”, which was first popularized during the COVID pandemic, describes a behavior pattern that goes back even further than that – at least to the dawn of social media. If you’ve ever found yourself scrolling your Facebook timeline for the fifth time in an hour, re-reading the same (often negative) posts because your brain is hooked on checking for a tiny drip of new information, you’ve participated in the phenomenon. It’s closely tied to FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out), a term coined in 2004 just as the internet was really finding its place in the hearts and minds of people around the world.

What’s changed in recent years is the sheer scale of it. Our ancestors might have worried about their town, their family, their crops. We, on the other hand, are handed an endless feed of every war, every disaster, every outrage – filtered through algorithms designed to keep us hooked. There’s a strange social pressure to stay informed about everything, as if not knowing about a faraway tragedy makes us complicit or self-absorbed. But is this constant exposure actually increasing our depth of compassion – or stretching it too thin to be useful, at the expense of our spiritual and mental health? When everything feels urgent, it’s hard to tell what actually deserves our attention. Our desire to stay deeply informed about the world can end up making our empathy surprisingly shallow.

Doomscrolling is Not a Side Effect

It may seem like our tendency towards doomscrolling is just an unfortunate, unforeseen side effect that came along with the devices and platforms that are now so ubiquitous. But, unfortunately, in many cases, this addictive nature isn’t a bug – it’s a feature.

In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari argues that we didn’t lose our attention spans to smartphones – they were taken from us, on purpose. Social media has been meticulously designed to hijack our focus so that we spend more and more of our time in an endless cycle of scrolling and reacting, without even pondering the source of our totally spontaneous reactions.

It’s as if they’re taking behavioural cocaine and just sprinkling it all over your interface and that’s the thing that keeps you like coming back and back and back.

Behind every screen on your phone, there are generally like literally a thousand engineers that have worked on this thing to try to make it maximally addicting.

– Aza Raskin, inventor of “infinite scroll”

Aza Raskin invented infinite scrolling – this is the feature that lets you endlessly scroll through apps like Facebook without ever clicking a “next page” link. He originally saw it as a convenience. But over time, as we see from the quote above, he’s acknowledged that what began as a usability improvement quickly became profit engine. Companies realized they could use it to keep people glued to their screens longer, even against their will. This, in turn, generates more engagement – and more ad revenue – in the process.

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

It’s not just that we’re being driven to gaze into our screens more and more, but also how much we’re being asked to carry. In today’s world, being “informed” no longer means knowing what’s going on in your town or even your country.

Instead, it means keeping up with the entire world, in real time, at the relentless pace of a 24/7 news cycle. To be seen as a good and intelligent person, you’re expected to stay constantly tuned in to the world’s pain.

Through most of human history, our circles of community – and therefore, our circles of empathy as well – were limited to about 150 people. Anthropologists like Robin Dunbar have argued that this was the natural limit for stable human relationships. Global events still reached people, of course – wars and rumors of wars, plagues, famines – but news from faraway places came slowly. It gave people space to process, without overwhelming their daily lives.

In a village of 150, bad things would absolutely still happen: violence, death, disease, and everything else that defines the burdens of the human condition. But the scale was more manageable. For example, using today’s crime rates, a village of 150 people might experience one murder in an entire century. Compare that to our experience today, where U.S. media exposes us to gruesome details carefully selected from an average of 68 murders per day. The rate of suffering isn’t necessarily higher – it’s the scale that’s disorienting. We weren’t built to carry this much, this often, about so many.

It’s no wonder that exposure to all of this bad news is bad for our mental health. Our brains are built to see surges of bad news as an existential threat. While we are certainly facing serious global issues that need to be thoughtfully addressed, studies also show that people greatly overestimate the risk of many dangers, likely due in part to overexposure through media.

This is where empathy fatigue creeps in. When everything feels urgent, it can be harder to care deeply about any one issue. When we are making a daily effort to stretch our compassion across billions, it can be harder to be truly empathetic on a local, personal scale. It’s not wrong to care, and we don’t need to shut ourselves off from the world in a state of blissful ignorance. But trying to carry everything, everywhere, all at once isn’t sustainable.

Empathy Spread Thin

The concept of empathy fatigue is not a new one, but it’s finally getting the attention it deserves as we wrestle with what it means to be a caring person in a world like ours. In short, empathy fatigue is a form of exhaustion (both emotional and physical) that comes from prolonged exposure and engagement with suffering or trauma.

Personally, I see a quiet danger in living in what I call the global shallows of empathy. When I’m constantly aware of horrible things happening across the world, I find that the struggles of people I actually encounter – friends, neighbors, even myself – can start to feel small by comparison. My own burdens, even when they feel almost unbearable, can also seem trivial.

If I’ve built a world where I can be deeply moved by the plight of those on another continent (which isn’t a bad thing, to be clear), yet feel impatient or emotionally unavailable toward the pain in front of me – even the struggles of those that I love the most – then I’ve spread my empathy too thin.

I recently came across these words from Ierom Serafim:

If you think you are helpful while you are consumed by anxiety and worries […], if you think you are helpful while you internalize the anger and the hatred that rules the world around us, then you are really deluding yourself.

That quote hits hard. It reminds me that there’s more than one way to drift into the shallows. If I do care about making the world a better place, I need to find a way to move beyond just looking at the news and being anxious or angry about it. That, alone, doesn’t do anything other than embitter me and reduce my ability to be compassionate to those around me. And when I stay stuck in that cycle, it only wears me down and makes me less present to the people who need me most.

A Contemplative Worry Tree

Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.

Philippians 4:6-7 (NIV)

Most world religions admonish followers not to worry, or at least offer a path for stepping out from under the weight of anxiety. But despite our best intentions, we’re human. We do worry. And regardless of how we feel about social media or the nonstop news cycle, we’re bound to encounter headlines about pain and suffering around the world.

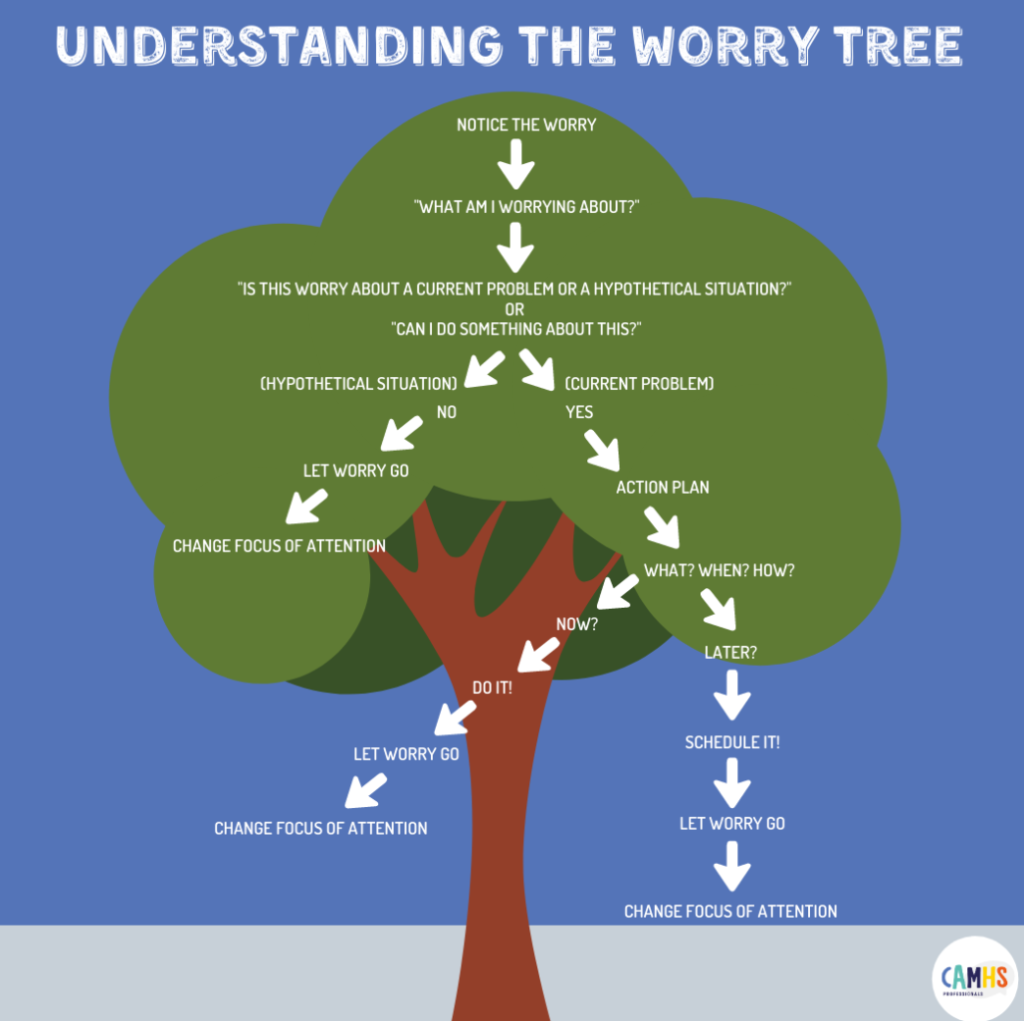

This brings to mind for me the idea of the worry tree, pictured below:

The worry tree offers a structured way to process the worries and anxieties we face in everyday life. It’s useful across a wide range of situations – from minor inconveniences to life-altering crises. I also think it offers a helpful framework for deciding where to invest our empathy in a more contemplative way. It invites us to step back from the global shallows and instead dive deeper where our compassion can truly make a difference.

One of the key decision points – especially when it comes to doomscrolling and the flood of fear or outrage on social media – is the question: Can I do anything about this?

More often than not, if we’re honest, the answer is no. No, I can’t personally resolve this war, fix this disaster, or dismantle this system. I can feel angry. I can carry anxiety throughout my day. But if I believe that my anger or worry somehow helps the situation, I’m deceiving myself.

I understand that some may push back on this perspective. That it’s vital for people to care deeply about politics, justice, and global issues – and I agree. I’m not trying to diminish the importance of activism, or praying for those in need, or supporting public awareness. But many of us – myself included – confuse feeling something with doing something. We mistake our emotional reaction for meaningful action.

And even if we do take concrete steps to help address the global problem that is causing us anxiety (which again, can be a very good thing), it’s likely that once we’ve taken action, we’d benefit from signing off of social media for the evening – reading a good book, enjoying a cup of loose-leaf tea, and soaking up the beauty of the sunset. Once we’ve mindfully done our part, ruminating on negativity doesn’t increase our compassion or effectiveness.

Instead, we’re invited to turn our attention back to our daily lives – to the people around us, to the beauty and the suffering we’re immersed in, to our local village. That’s where our empathy can take root and grow.

Presence and Communal Depth

In a world that tempts us to know everything, care about everything, and fix everything, perhaps the most powerful thing we can do is to be present. The illusion that we can stay in control by knowing everything – and, similarly, that anxiety is the same thing as empathy – is at the heart of doomscrolling and the global shallows.

But presence, especially in the form of embodied compassion, offers a different way. Unlike the endless demands of a global population, the needs of our ancient-sized communities – our families, our neighbors, our local villages – are much more manageable, even during the toughest of circumstances. Tools like the worry tree can help us pause, breathe, and better contemplate where our attention and compassion is truly needed. And when we release what we cannot control and turn with care toward the people right in front of us, we find something unexpected: not withdrawal, but renewal. A deeper kind of empathy. A grounded, paradoxical peace. The kind that quietly changes the world, one heart at a time.

Discover more from inquiring life

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.