There are more real numbers between zero and one than there are atoms in the entire known universe – and somehow, that’s only the beginning. Infinity isn’t just big. It stretches our ability to understand the fabric of space and time. It unsettles philosophers, challenges scientists, and even makes its way into video games.

Infinity first caught my attention when I was a kid. I was entranced by the never-ending staircase in Super Mario 64, where no matter how far you ran, you didn’t get any closer to the top unless you had reached a certain milestone in the game.

I didn’t know much about math or philosophy back then (to be fair, I still don’t know that much), but something about it stuck with me. It made me start to question what people meant when they talked about things like eternity, or when I heard in Sunday school that God was “infinite.” Was that just a fancy way of saying “very big,” or did it point to something real – something even more mysterious and unending than that staircase?

As I got older, I noticed most people didn’t like to think much about infinity. It was easy to brush off, as if it was just a silly thought experiment and not something worth thinking about. But I also started to sense a kind of unease beneath the dismissal. When I asked questions or tried to have discussions about infinity, people would usually shift the conversation or laugh it off, like the topic made them uncomfortable. And I get it – because when you start to really consider what infinity implies, not just as an idea but as a possible structure behind our reality, it blurs the lines between what we know, what we believe, and what we can’t explain.

That’s what this post is about: a journey into the idea of infinity – not primarily to make an effort at explaining it, but to explore how it shapes our view of existence. We’ll begin with a brief look at how humans across time have wrestled with the infinite, from ancient philosophers and theologians to modern mathematicians and cosmologists. And then, we’ll step into deeper waters.

Infinity’s Origins: How Ancient Paradoxes Still Echo Today

The idea of something unending isn’t new. Long before the word infinity entered philosophical vocabulary, ancient cultures were already reaching for ways to describe what couldn’t be measured or contained. The Egyptians distinguished between two kinds of eternity – one linear, the other cyclical– using them to express the divine patterns of the cosmos and the unbroken flow of the afterlife. Hebrew scriptures spoke of a God existing “from everlasting to everlasting,” hinting at a presence beyond time itself. In India, early Vedic hymns described reality as ananta – without end – and imagined time as a wheel with no beginning.

None of these traditions used the language of set theory or mathematical abstraction – but they all shared an intuition that the world we see rests on something endless. Whether imagined as a divine being, a sacred rhythm, or the unending expanse of the heavens, the infinite was already whispering at the edges of human thought.

That whisper took on a new shape in ancient Greece, where early philosophers began not only to sense the infinite, but to name it. In the 6th century BCE, Anaximander introduced the concept of the apeiron– a word meaning “the boundless” or “the indefinite.” For him, the origin of all things couldn’t be something ordinary or limited; it had to be something without edges, without form, and without end. This marked a turning point: a shift from spiritual intuition to philosophical exploration, where the infinite, still a sacred mystery, was also a concept to be examined.

Aristotle responded by drawing a crucial distinction that would shape thinking for centuries. He accepted the potential infinite – like the process of counting, which could continue forever – but firmly rejected the actual infinite, meaning a completed, infinite quantity or set. In his view, treating infinity as something that could actually exist led to insolvable paradoxes, and was to be carefully avoided.

This cautious approach began to shift in the 17th century with the English mathematician John Wallis. In his 1655 work Arithmetica Infinitorum, Wallis introduced the symbol ∞ to represent the idea of an unbounded quantity. Though he didn’t fully formalize infinity as a mathematical object, he helped prepare the ground by giving it the symbolic foothold it still has today.

But it was Georg Cantor, in the late 19th century, who would radically redefine the concept. Cantor developed set theory and showed that infinities could be rigorously compared and even ordered by size. He demonstrated that while the set of natural numbers (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. to ∞) is infinite, the set of real numbers between 0 and 1 (e.g. 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 etc. to ∞; 0.2, 0.02, 0.002, 0.0002, etc. to ∞; and so on) is more infinite – uncountable. Despite initial resistance by contemporaries, his work became the basis for modern mathematical analysis, and his insights revealed that infinity has a structure, with its own logic, patterns, and coherent depth.

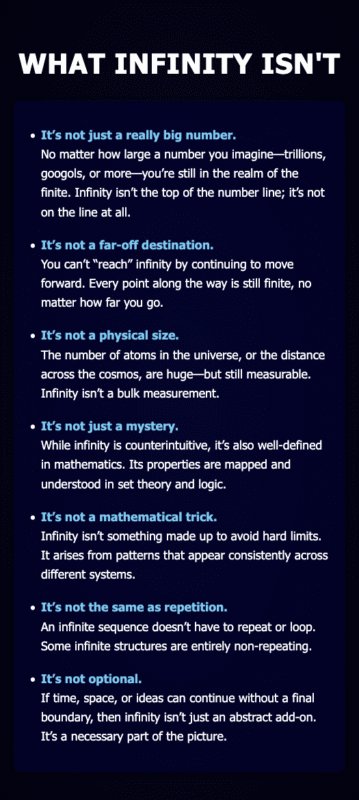

Defining Infinity by What It’s Not

We often say “infinity” when we’re really imagining something vast. And most of the time, that works well enough; we intuitively sense that it implies something fundamentally different than “very large.” But when we try to picture it, our minds often default to what they can handle: big numbers, long spans of time, and far distances.

We even treat some ideas as if they’re infinite, without always thinking through the implications. Most religious traditions, as we discussed above, describe God as eternal – without beginning or end. Many cosmological models propose that the universe, or whatever underlies it, is infinitely old, since something can’t come from nothing (side note: the Big Bang theory outlines how the universe unfolded, not where it came from. It sidesteps the deeper question of why there’s something rather than nothing). But in daily life, we tend to toggle between “infinite” and “really big,” depending on what feels manageable. We rely on a kind of mental blur: eternal and infinite when it comforts us or explains away difficult philosophical questions, finite when we need to lean on an idea that feels more concrete.

These ideas are tempting mental shortcuts – but each one quietly leads us away from what infinity actually is.

But what happens when we press that blur into something sharper – when we follow either path to its conclusion?

Accepting the infinite means accepting that time might stretch in both directions, not just endlessly forward but infinitely back as well. And when infinity runs both ways, it carries a deeper implication: the pattern must be either cyclical or self-sustaining, or else it would have already unraveled. A sequence that has lasted forever can’t be fragile or temporally bound.

And yet, rejecting infinity leads us somewhere just as strange – to the claim that there was once nothing. Not darkness. Not vacuum. Not empty space. Nothing. And if that was the case… out of that nothingness, everything came to be.

Either way – infinite existence or absolute emergence, a materialistic reality or a spiritual one – we’re living in a universe that defies ordinary logic.

Infinite Optimism and Boundless Possibilities

Infinity can feel like an abstract curiosity – the kind of idea that belongs in a math class, not in real life. Honestly, I understand why many people are quick to change the subject. However, from what I’ve learned so far, I’m convinced infinity isn’t just theoretical. It has real implications for how we understand progress, the future, and our origins. Whether you approach life through science, faith, or something in between, the infinite confronts you with questions that cut to the core.

But it can also feel exhausting. In a universe that may be infinite, blind, and impersonal, where our planet is a speck and our lifetimes are just a blink compared to cosmic timescales – what do our individual choices even mean? Moral nihilism, the idea that meaning and morality are illusions in the face of cosmic indifference, often draws strength from the same concept of infinity.

One answer comes from physicist and philosopher David Deutsch. Deutsch is one of a growing number of thinkers who see the infinite not as an irrelevant abstraction or a source of despair, but instead as the foundation for long-term hope and rational optimism. Best known for his pioneering work in quantum computing and for his book The Beginning of Infinity, Deutsch argues that here we find hope for real progress that, eventually, will far surpass what we can now comprehend. In his view, the universe – and by extension, the multiverse – invites us to grow, indefinitely. He is not a religious person and makes his case from a purely secular worldview, but his thoughtful reflections are just as profound for those who have a more spiritual outlook.

Deutsch’s core claim is a bold one: with the right knowledge – or as some would say, the right information – anything not expressly forbidden by the laws of nature is possible. There’s no natural ceiling to what can be understood, solved, or improved. Similarly, there is no final level of moral development, no perfected style of art, no optimal human experience that marks the end of growth. Moral systems, educational ideals, even beauty itself – these are all frontiers that can evolve without limit. We’re not living at the end of some grand historical arc, Deutsch argues. We’re still extremely close to the beginning – and we’ve barely scratched the surface of what’s possible.

For those of us with a spiritual or Christian worldview, Deutsch’s vision may not capture the full picture – but it still resonates in profound ways. The idea that progress has no ceiling, that truth is discoverable, and that meaning can deepen endlessly all echo core spiritual themes. Christianity speaks of eternity not as a static afterlife, but as life made more abundant in union with God. Where Deutsch sees the universe inviting us to grow in knowledge and creativity, the Christian tradition sees that invitation coming not from an impersonal cosmos, but from an infinite and deeply personal God – a Creator who, in time, will do immeasurably more than humanity could ever ask or imagine.

While secular and religious views may differ in their framing, they share a significant common thread. For Deutsch, knowledge is the ultimate driver – impersonal, self-correcting, and open-ended. For Christians, the infinite includes not just the pursuit of truth, but its embodiment in the person of Christ. Growth is not merely cognitive, but relational. Yet both views, in their own way, reject the victory of death. Both insist that the story continues – and that where we are now is only the prologue.

Selfhood in an Infinite Story

If growth and discovery have no upper limit, the consequences turn inward as well – not just into the progress we achieve, or the gifts God may offer us, but into the very core of who we are. Not just immeasurably more for us, but in us. Whether we imagine a future where humanity evolves alongside amazing new technology, or a cosmos where divine transformation works within every soul, infinity ultimately touches us all.

This brings us to the question of selfhood. What does this mean for who we are – and who we might become?

The idea that the self is part of an ongoing story – capable of growth, transformation, and renewal – is not new. It runs through both secular and spiritual traditions, from ancient philosophies to modern theories. Whether described in the language of scientific progress, sanctification, enlightenment, or discovery, the intuition has always been there: our growth and maturation are not complete at adulthood, or even at the end of our lives. Instead, we are meant to change and become more. What that transformation looks like, however, is imagined in many different ways – and the way we understand it changes how we live, grow, and hope.

Among speculative scientific ideas, quantum immortality offers one of the most startling reflections on the persistence of personal existence. In simplified terms, if the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is true, then every possible outcome branches into a new reality – and for any conscious observer, there would always be a timeline where survival continues. Some theorists, like Alexey Turchin, argue that this points toward a form of multiverse immortality, where the conditions necessary for continuity depend not just on quantum mechanics, but on how we define personal identity itself. An established and growing group of theorists are taking seriously the idea that consciousness – and perhaps our personal, individual storylines – might persist indefinitely across branching realities.

Another vision of personal continuity comes not from quantum physics, but from advances in computing and cognitive science. The idea of mind uploading – preserving or transferring aspects of consciousness into digital or alternate substrates – challenges traditional boundaries of selfhood. If a mind can be copied, extended, or hosted in new forms, what remains truly “us”? Are we bound to our biological origins, or can identity adapt and expand without losing its essence? These questions, though still firmly in the realm of speculation, are becoming increasingly relevant as technology advances – and projects such as Neuralink allow mind and machine to grow increasingly intertwined.

This leads to a deeper possibility. In The Beginning of Infinity, Deutsch proposes that people – like computers being Turing-complete – are universal constructors. That is, with the right knowledge and tools, we’re capable of solving any problem that is not forbidden by the laws of physics. This means that properly aligned AI systems (don’t forget – The Singularity is coming!) wouldn’t replace us – they’d extend our capacity to build, discover, and grow. Progress would, in this view, be something we participate in, unendingly.

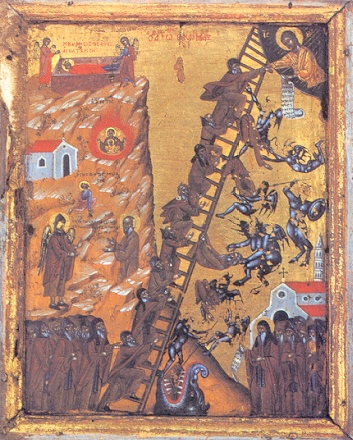

In spiritual traditions, especially in Eastern Christianity, this kind of transformation is already part of the vision. Theosis – or deification – speaks to the ultimate destiny of every person: not merely to live better lives, but to share in the very life of God. Theosis, for Orthodox Christians, is not a static state achieved after death, but a lifelong (and eternal) movement of love toward God, beginning with baptism and continuing through prayer, sacramental life, and transformation of the heart.

This vision of infinite growth is not unique to Orthodoxy. Many Christian traditions envision heaven not as a static perfection, but as an eternal unfolding – an endless deepening of joy, knowledge, and love in the presence of God. The Orthodox tradition, in particular, emphasizes that human fulfillment comes not through erasure of individuality, but through its perfection. God’s love does not erase us; it reveals and elevates our true selves. In Christ’s incarnation – where humanity and divinity are united – we are shown both our model and our future: to become partakers of the divine nature, as Saint Peter wrote, and to grow endlessly in the likeness of God.

This stands in meaningful contrast to some secular visions of infinite continuity, such as our earlier examples of mind uploading or quantum immortality. While these ideas imagine the extension of consciousness across time, they often treat the self as primarily informational – a pattern to be copied, preserved, or transferred. In the Christian vision, the infinite journey of the self is not just about survival or replication. It is about communion: a dynamic, ever-deepening relationship with the Source of all being, where growth is fueled by love, freedom, and transformation rather than mere continuity or technological progress.

Whether viewed through the lens of faith or of science, the idea of an infinite story of selfhood is not just a thought experiment – it is (and long has been) a serious part of how humanity envisions the future. On one side, the spiritual tradition calls us to endless growth in love, wisdom, and communion with the divine. On the other, emerging technologies raise new possibilities for extending consciousness, transforming identity, and challenging our deepest assumptions about what it means to be a person. As advances in AI, neuroscience, and physics accelerate, we may find ourselves living in a world where truths from both realms – spiritual and secular – intersect in ways we can barely imagine today. Navigating that future will require a deep humility: a willingness to hold awestruck wonder and cautious wisdom in a delicate balance together, and to walk forward into the unknown with both courage and thoughtfulness.

This brings us naturally to the next step: exploring some of the practical implications of these ideas – not just for hypothetical far-off futures, but for how we live, grow, and hope here and now.

Living with Infinity in Mind

Infinity can feel abstract – something only relevant in theory – yet it carries concrete weight. Physicists estimate ≈10²⁴ stars in the observable cosmos and perhaps 10⁸⁰ atoms overall; on that scale a single human life is vanishingly small. And not only are we small, but we can’t ever know everything, either. In 1931 the logician Kurt Gödel demonstrated that any logical system rich enough to handle arithmetic will contain true statements it can never prove – a result now called Gödel’s incompleteness theorem. It reminds us that even the surest proofs leave something unproven. Dare to let that vastness reinforce your humility and widen your curiosity.

When we view our existence through the lens of infinity, the improbable can become seemingly inevitable. Physicists, for example, point out that in an eternal cosmos random quantum fluctuations could assemble a momentary self-aware “Boltzmann brain,” while the Poincaré-recurrence theorem says that any finite system left running long enough must eventually cycle back through its earlier states. Even the “arrow of entropy,” which drives matter toward disorder, coexists with islands of increasing complexity such as stars, cells, and minds. Together, these ideas remind us that reality doesn’t care about conforming to our tidy narratives. Stand at the frontier of the unknown with wonder rather than fear.

Infinity also blurs the boundary we draw between faith and science. Astronomers press outward because, as Edwin Hubble wrote, “[t]he history of astronomy is a history of receding horizons,” and there are always new discoveries to be made beyond what we can see today. On the contemplative side, writers such as Gregory of Nyssa (4th century) and Julian of Norwich (14th century) pictured heaven as an everlasting ascent: the soul grows closer to God forever, yet never exhausts His depth. Set alongside David Deutsch’s claim that anything not forbidden by physics is possible, these voices suggest a shared outlook: the frontier is open, whether one seeks further knowledge of the universe or deeper communion with God. Hold reason and reverence together; let each discipline keep the other honest.

Good and evil both increase at compound interest. That is why the little decisions you and I make every day are of such infinite importance. The smallest good act today is the capture of a strategic point from which, a few months later, you may be able to go on to victories you never dreamed of. An apparently trivial indulgence in lust or anger today is the loss of a ridge or railway line or bridgehead from which the enemy may launch an attack otherwise impossible.

C.S. Lewis – Mere Christianity

On an infinite stage, even small choices matter. In Game Theory, the Folk Theorem shows that, with repeated interactions, a wide range of cooperative strategies can outperform selfish/individualistic ones, provided the players take the long-term outcome into account. Likewise, chaos theory (think Lorenz’s “butterfly effect”) teaches that tiny changes can cascade through a system with unlimited reach. A single act of love or insight, then, can ripple across the universe without end – so live as though the choices you make will outlast you. Live as if every decision carries echoes you may never hear – but that eternity will.

Journeying Together on the Endless Sea

We sail waters without edge, on journeys without end. And though the sea stretches far beyond sight, we are not without companions – or without hope.

Along the way, we have glimpsed how humans first wrestled with the infinite: from the ancient contemplations of Anaximander and Aristotle, to the unfolding mathematics of Cantor and Wallis, to the modern recognition that infinity is not merely a concept, but a force that shapes our understanding of existence itself – a force that is sometimes easier to define by reminding ourselves what it isn’t. We waded into deeper waters with Infinite Optimism – where thinkers like David Deutsch remind us that progress, creativity, and life itself may have no natural limit. We explored how selfhood, both secular and spiritual, can unfold endlessly, inviting us not just to survive but to grow into richer, truer versions of ourselves. And we reflected on how living with infinity in mind reshapes the choices we make today: calling us toward humility, wonder, patience, bravery, and determination.

The journey is far from complete – but it seems it never was meant to be. In an infinite story, the act of becoming is itself the mode of transport, and the perpetual destination all at once.

And you are already in that story. Whether you believe this story is from the universe, or from God – we know it is stranger, richer, and more generous than any of us can yet imagine. Let’s stay curious, stay humble, and keep our hearts open to a greatness that could outshine every expectation as we sail this endless sea together.

Discover more from inquiring life

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.