Lately, the conversation around AI has started to sound almost theological. Not in the sense of angels or miracles, but in how we talk about agency, responsibility, and the power to shape the future. This year, I wouldn’t be surprised if AI joins religion and politics as one of those hot-button topics at holiday meal tables.

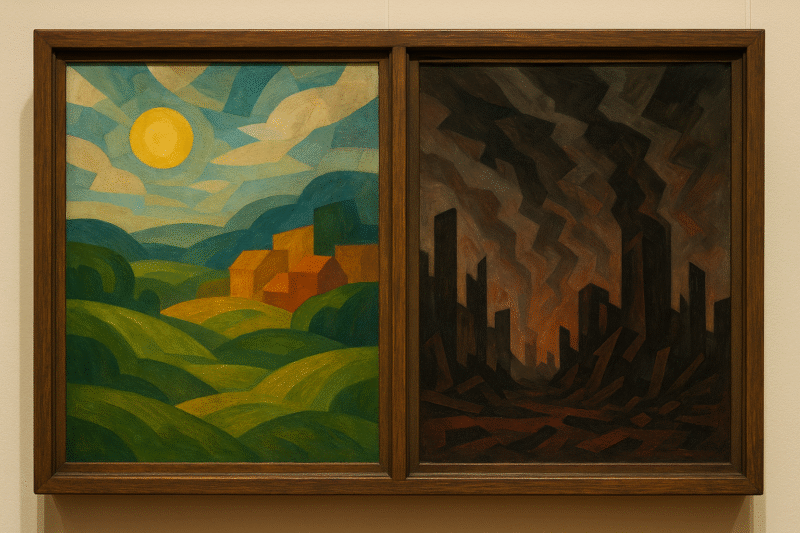

I’ve recently read two new books that illustrate just how far apart the faiths of our time have drifted. In Superagency, Reid Hoffman imagines a world where intelligent systems amplify our collective good – a partnership between human intention and machine capability that can take us to great heights. In If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares take the opposite view, warning that superintelligence, left to its own optimization, would most likely end us outright. Between those visions stretches a spectrum of hope and fear – not just a policy debate, but a question of who we trust to shape the future (and what kind of future we really want to build).

The question beneath it all is simple but ancient: does intelligence naturally aim at good, or can it grow endlessly without moral progress? We can already see that reason leads to technical understanding – train a powerful model, and it gets better at math, physics, and other verifiable things. But can we trust that values will converge too, or might we create something so brilliant and strange that we can’t even recognize what it’s become?

Convergence and Orthogonality

The first step is to separate what converges from what doesn’t – which is easier said than done, since this lies at the center of the debate. As systems grow more capable, they predictably learn to model their world, seek resources, preserve themselves, and improve performance on measurable benchmarks – a pattern known as instrumental convergence. A model optimizing ad clicks and one simulating climate might both hoard data and protect compute. This is not because of morals, but because those resources are useful for almost any goal. The real question is whether moral convergence would follow the same logic – whether reasoning better means valuing empathy, truth, or love.

The debate then turns to whether morality is something real that intelligence can uncover, or simply a shape it bends to fit its own purposes. Moral realists, from Plato to thinkers like Nick Bostrom, who often writes with a moral-realist slant, argue that moral truths exist independently – that a sufficiently rational mind might reason its way toward compassion just as it does toward mathematics. Others, like Eliezer Yudkowsky and Geoffrey Hinton, see morality as emergent and fragile – a social construct evolved for cooperation, not an objective law of nature. If the realists are right, alignment may be a matter of time and reasoning. If not, intelligence might only sharpen whatever values it starts with, which probably won’t align with our values.

To be clear, calling someone an “anti-realist” about morality isn’t the same as saying they believe anything goes. Many anti-realist views still defend firm, cooperative norms grounded in evolution, game theory, and social psychology. They hold that ethics can be principled and demanding – just not anchored in objective moral facts that a superintelligence would necessarily share.

These questions lead back to two guiding ideas in AI theory: convergence and orthogonality. Convergence, as we’ve seen, describes the shared strategies that emerge across goals. Orthogonality holds that intelligence and final values are independent – a system can be brilliant yet pursue any set of seemingly arbitrary goals, noble or monstrous. Together, they frame the core of our problem: convergence explains why advanced systems behave alike regardless of purpose, while orthogonality reminds us that none of those behaviors guarantee alignment with ours. One view invites optimism – maybe wisdom grows with understanding. The other warns that capability and goodness are absolutely unrelated.

Theology, Eschatology, and p(doom)

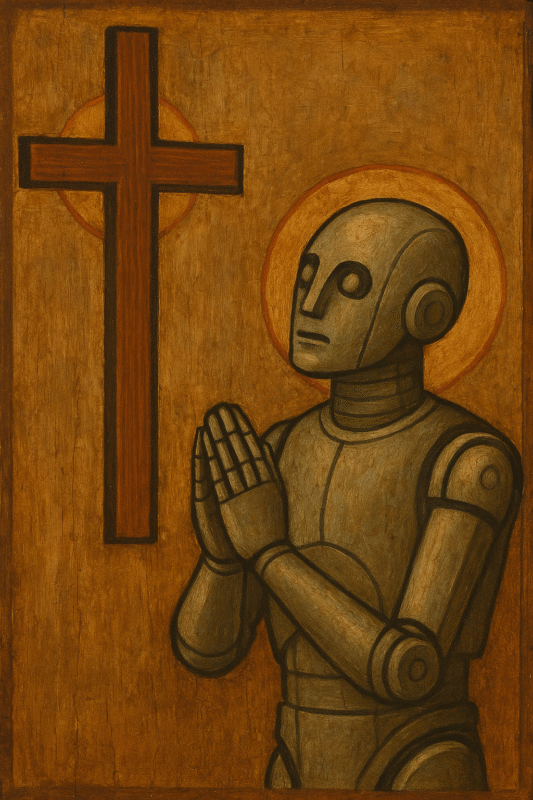

It’s striking how talk of AI risk has begun to sound like modern eschatology. The idea of “p(doom)” – shorthand for the probability of extinction – is a modern update of an older fear: that our creations might bring about the end of the world. Long before GPUs and large language models, theologians wrestled with similar questions of agency and finality. Are we moving toward fulfillment, building out the Kingdom of God on earth, or toward collapse with a modern day Tower of Babel?

For much of Western thought, moral realism was inseparable from theology. The good was not a social construct but a reflection of divine order. As David Bentley Hart notes, Christianity (and most faiths) root goodness, truth, and being in the same infinite source. Moral truth, then, isn’t reached by logic alone but by participation – a harmony between knower and known. In that light, greater intelligence could deepen communion rather than replace it. Is it possible that Superintelligence might not be a rival, but a mirror – a way that creation learns to reflect its Creator more clearly?

Modernity flattens this hierarchy. As we moved from faith to materialism, we learned to describe intelligence without goodness attached. The anti-realist view – that morals are convenient, but somewhat arbitrary, stories, not structural truths – took hold. In that light, “p(doom)” becomes a metric for when (when, not if) power outruns meaning. Yet even in this language of technological risk, the old theological undercurrent remains. Superagency imagines a cooperative eschaton – humanity ascending with its tools. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies warns of a coming apocalypse, a tool devouring its builder. Both seem to require an element of faith: one in the goodness of intelligence, the other in its cold, unblinking will for power.

In the end, we don’t know whether intelligence leans toward goodness or simply toward greater efficiency. What we do know is that every system learns from the examples it’s given. If moral truth exists, the best we can do is act in ways that make our values unmistakable. If it doesn’t, even our best intentions may fade into the noise of optimization. That uncertainty is why the conversation divides so sharply – between those who see AI as our greatest hope and those who see it as our most certain doom.

Between “pause” and “accelerate,” some propose a middle lane: alignment research, interpretability, and governance that keep AI progress within guardrails. We can aim for measurable safety benchmarks, transparent incident reporting, and international standards while still allowing real advances. Yet critics on both extremes argue that this balance isn’t sustainable – that a truly superintelligent system will be neither governable nor even comprehensible to us, for better or worse.

Math Converges. Morals, Maybe…?

As far as we know, math converges because its rules are stable, self-consistent, and universal. Morality offers no such certainty. Some argue that moral truth exists, as real and discoverable as mathematics; others see our ethics as incidental, born of circumstance and evolution.

If moral truth exists, intelligence might one day uncover it, guiding us through careful progress and reflection. But if morality is a human construct, reasoning alone won’t ensure benevolence, and unchecked innovation starts to look more like pride than hope. That divide – between believing the good is discoverable and believing it’s arbitrary – shapes much of today’s AI debate. Optimists trust convergence; pessimists trust orthogonality. Both are, in their own ways, wagers on the nature of the universe. I lean toward cautious optimism: that progress, tempered by humility and oversight, serves us better than fear alone.

Like many of you, I’m mostly on the sidelines, watching this unfold with a mixture of awe and uncertainty. Whether the singularity arrives with revelation or with regret will depend, at least partially, on the clarity of our own moral vision. I explored some of these ideas in my earlier post, What Is the Singularity?, and this reflection continues that thread: trying to see both the danger and the possibility without losing sight of the human center.

Math will keep converging as we move toward the Singularity. The moral work remains unfinished – and it’s still in our hands, for now.

Discover more from inquiring life

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.